More allusions to King Arthur in RDR2.

All articles on this site feature detailed discussion of literary allusions in Red Dead Redemption 2, and as such contain unmarked major and minor spoilers for the game, and occasionally the eventual fates of some characters in Red Dead Redemption. Read at your own risk.

The remaining allusions to King Arthur in RDR2 that didn’t fit into essays elsewhere: what’s up with Kieran’s beheading, why Arthur sees a deer in his honor visions, Pleasance, and much more.

The other Arthurian essays:

- Death of a Golden Age: Arthurian Legend and Red Dead Redemption 2

- “A Loving Act”: The Grail in Red Dead Redemption 2

- Negative Images: Arthur Morgan and Micah Bell III

- Love Kills: Arthurian Characters in Red Dead Redemption 2

Names

Percival. One of King Arthur’s best knights, and often the one who achieves the Holy Grail, is named Percival. In addition to the many parallels I’ve discussed, Red Dead Redemption 2 also features a character named Percival in the magic lantern show “One of the Wonders of the Age.” This Percival’s father was an inventor who crashed his flying machine into a lamp and died in the resulting fire. Like Dutch, the inventor father was a victim of his own hubris. Mrs. Hobbs also named one of her art pieces Percival. RDR2 often repeats names to draw attention to allusions (for instance, with Annabelle).

Leviticus Cornwall & King Cornwall. Leviticus Cornwall’s last name is taken from the medieval poem “King Arthur and King Cornwall.” Like Leviticus, King Cornwall is extremely rich. King Arthur and some of his knights go to see him in disguise, and the king speaks insulting of Arthur at some length. The knights rob him of his most valuable possessions, and Arthur kills him in revenge for the insults. One of the allusions to King Arthur in RDR2 is Dutch Van der Linde’s murder of Leviticus Cornwall. As previously discussed, Dutch is more similar to King Arthur than Arthur Morgan is.

Themes

Grief. The dominant tone of RDR2 is one of mourning. Naturally, one of sources the writers used was one of the most mournful renditions of Arthurian legend: Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King. The last poem in the story cycle, “The Passing of Arthur,” contributes to the main story’s ending imagery. During King Arthur’s final battle, Tennyson writes, “A deathwhite mist slept over sand and sea” (95) and “friend and foe were shadows in the mist” (100). Toward the end of “Red Dead Redemption,” a mist rises, making the forest haunting and strange.

In the battle, Modred (Mordred) strikes Arthur on the helm (if low-honor Arthur helps John get to safety, Micah will shoot him in the head). Arthur, dying, orders his knight Sir Bedivere to throw his sword Excalibur into a nearby lake. Although he initially intends to obey, Bedivere hides the sword. When he returns, Arthur knows he hasn’t really thrown it in. Bedivere tries again, but after wrestling with himself, he hides the sword once more. While the sword is highly valuable, Bedivere doesn’t covet it so much as want it to be kept as a memento of the king. He thinks to himself:

What record, or what relic of my lord

Tennyson 266-277

Should be to aftertime, but empty breath

And rumours of a doubt? But were this kept,

Stored in some treasure-house of mighty kings,

Some one might show it at a joust of arms,

Saying, ‘King Arthur’s sword, Excalibur,

Wrought by the lonely maiden of the Lake.

Nine years she wrought it, sitting in the deeps

Upon the hidden bases of the hills.’

So might some old man speak in the aftertime

To all the people, winning reverence.

But now much honour and much fame were lost.

What this speech means is that his difficulty is about grief. His king and friend is dying, and he doesn’t know how to let go. Surely he can keep something. Surely he will not lose his friend entirely.

In RDR2, John Marston represents Bedivere. The setting is similar: Bedivere has to walk to the lake “By zigzag paths, and juts of pointed rock” (218). Arthur and John scramble up the side of a cliff as they try to escape. Like the king, Arthur has to give his order — in his case, to tell John to leave him — three times, the last time with particular force, before John will do it. He gives John the possession that most symbolizes him (his hat), although unlike Bedivere, John doesn’t have to throw it away.

The furious king gives his order a third time. Bedivere finally throws the sword, which summons a barge that takes Arthur away — perhaps to be healed, perhaps to die, perhaps to return one day. The final image of King Arthur figures in the game as well: the barge bears him off “till the hull/Looked one black dot against the verge of dawn” (439). The poem closes: “And the new sun rose bringing the new year” (469). We see Arthur silhouetted against the rising sun as he dies.

Brother battle. The mythological archetype of the brother battle is a major component of both Red Dead Redemption and Red Dead Redemption 2. We see it in the development of Arthur’s relationship with John (of particular note: “The Sheep and the Goats,” “The Battle of Shady Belle,” “Bridge to Nowhere,” “Red Dead Redemption”), Dutch Van der Linde’s relationship with Colm O’Driscoll, and the Stranger Mission strand “Oh, Brother.” Although this isn’t a direct allusion to Arthurian legend, the archetype is also an extremely prominent one there, and could make for an interesting comparative analysis (by someone who didn’t have quite such a mountain of material still to share).

The failed quest. When John gets a job at Pronghorn Ranch, he says Jack’s name is Lancelot. The odd choice of alias highlights a parallel: Lancelot also goes on the quest for the Grail, but is unable to achieve it. Similarly, through the efforts of his family, Jack is nearly able to get free of the cycle of violence in the first game, but ultimately fails.

Code of honor. The Knights of the Round Table swear an oath to follow certain standards of behavior, i.e., the codes of chivalry. In “Fatherhood and Other Dreams,” Mary disparagingly speaks of Arthur’s “code.” When questioning his own decisions in his journal, Arthur refers to “my whole code that I lived and killed by.”

Courtly love. Devotion in love is a core principle in Arthurian legend. In Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur, when Tristram marries a woman other than the one he’s in love with, Lancelot is livid — despite the fact that the woman Tristram is in love with is his uncle’s wife. When Lancelot hears about the wedding, he says: “let him wit that the love between him and me is done for ever, and that I give him warning, from this day forth I will be his mortal enemy” (208).

Arthur’s emotional devotion to Mary is built on this principle, as is his chastity, which Malory (among others) was fervent about. (Only chaste knights are able to find the Grail.) Arthur’s habit of calling his female friends “my lady” is an allusion to courtly manners. The rude way he speaks to the sex workers in “Americans at Rest” paints a sharp contrast with this behavior and characterizes his role as a Perceval figure early in his journey.

Cowardice. One of the most important attributes a knight must show is bravery. Cowardice is the gravest dishonor. Arthur calls Micah a coward in “An American Pastoral Scene” and when antagonizing him in camp. Chivalric principle explains why this is the insult Arthur chooses. It also paints Micah’s violence in a different light: Micah kills so readily because he’s afraid of being killed. For instance, he takes a cheap shot at Susan Grimshaw so she doesn’t get the chance to take a fair one at him. Fittingly, in Idylls of the King, Tennyson calls cowardice “the child of lust for gold” (“To the Queen”). Micah’s obsession with the Blackwater money is apparent as early as “Who the Hell is Leviticus Cornwall?”

Motifs and Symbols

The cauldron. As previously discussed, in the Second Branch of the Mabinogion, Bendigeidfran gives Matholwch a magical cauldron that will bring a dead man back to life if he’s put inside it. This is likely the inspiration behind the Witch’s Cauldron. Drinking from the cauldron will cause the player character to black out and respawn outside the hut with their cores refilled.

The Holy Grail has often been identified with various cauldrons from Celtic mythology (L. Jones 24). Leslie Jones argues that this isn’t a correct reading, but it may none the less be significant for our purposes. The question isn’t whether it’s correct historically, but whether RDR2‘s writers found that meaning resonant. Their choice to reprise Red Dead Redemption‘s Mother Superior Calderón may be meaningful. “Calder” means “cauldron” in Spanish. Sister Calderón is an important figure in Arthur’s journey to find redemption and achieve the game’s version of the grail.

The stag. The white stag is one of the most important symbols in Arthurian mythology. The stag is a call to adventure, but also often has spiritual significance. In Lancelot-Grail Cycle’s Queste, four knights see a stag turn into a man in a chapel; a hermit there explains that “the stag represents the resurrection of Christ through its rebirth” (McShane). Arthur sees a stag in his honor visions. In a sense, this stag is calling him on a journey (to death), but it also represents Arthur’s self-perception and emotional state, and is another instance of Arthur appearing as a Christ figure. As Mary Jones notes, the white stag “is also associated with the sun; in Christian iconography, the stag appears with the sun between its horns.” As Arthur dies, the sun and the stag together is the last thing he sees.

The stag that Arthur sees isn’t white, but that likely would have looked strange with the gold-drenched filter used in these visions. Many of the legendary animals – the elk, the moose, the beaver, the bison, the bull gator, the pronghorn, the ram – are white; these are likely an allusion to the white stag.

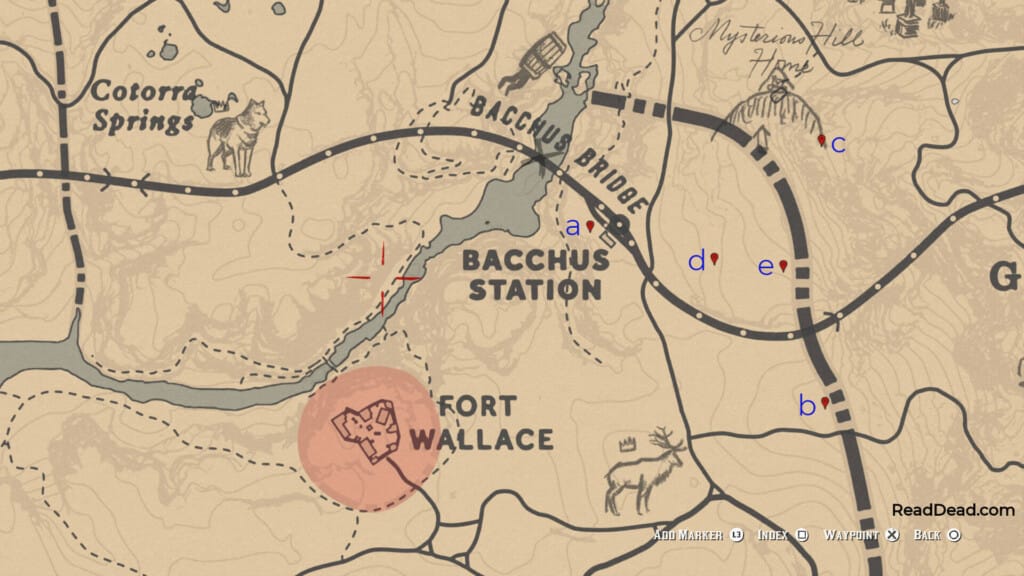

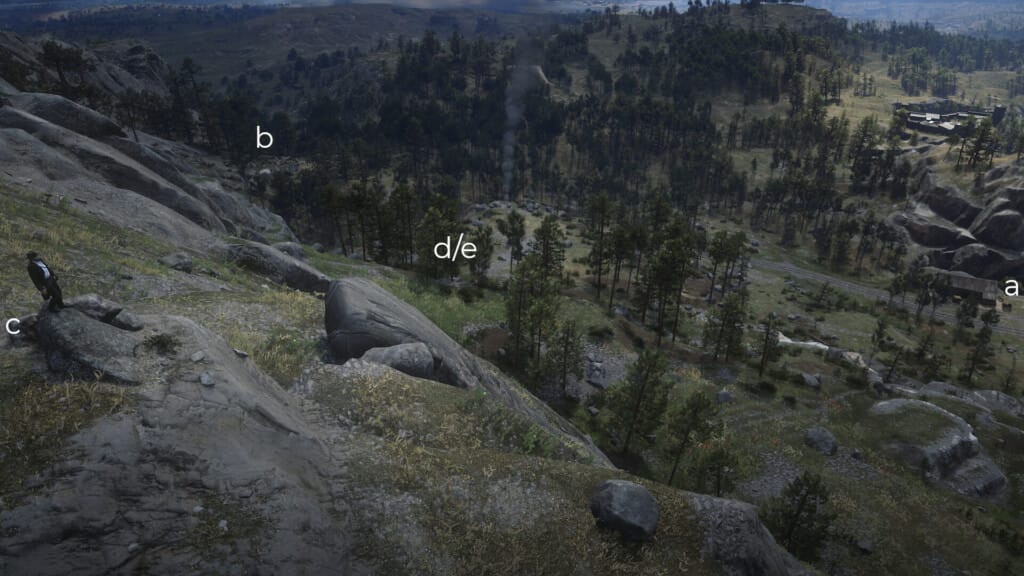

The most significant of these is the elk, which is a white stag. It spawns near Arthur’s grave, associating it with Arthur and his death. Its spawn location is not only below Arthur’s grave, but in the approximate center of a triangle created by the points where Arthur retrieves the chanupa (“Archeology for Beginners”), where he tells John not to look back for the second time (“Bridge to Nowhere”), and where he’s buried. This may or may not be significant, but given how close together these points are, and the fact that those missions are all particularly important to Arthur’s journey, it seems likely to have been intentional.

Beheadings. The game’s motif of beheadings is an allusion to the Celtic cult of the head (Davies 236), as well as the extremely frequent beheadings in Arthurian legend. It was the knight’s dispatch of choice. We see the motif with Kieran Duffy, Saint Denis (as pictured on the city seal), Arthur’s journal entry after “The Battle of Shady Belle” (he says Milton asked for “Dutch’s head on a platter,” an allusion to the Biblical myth of John the Baptist), and one of the bodies outside the Appleseed Timber Company clearcut. Saint Denis is named for Saint Denis of Paris, who was a cephalophore: a saint depicted carrying their own head. The same idea is found in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The Green Knight continues to live, speak, and walk after being decapitated.

Places

Valentine. The town of Valentine is partially named for a knight from Thomas Chestre’s poem “Sir Launfal.” Anne Laskaya and Eve Salisbury’s explanation of Sir Valentine makes his significance to RDR2 obvious:

“The narrative of Launfal, [Lee C.] Ramsey claims, expresses a fantasy solution to the tension between community and individual drives and desires: ‘By a natural extension of the family-romance myth, this could be achieved by rejecting (slaying) the civilization emblemized as father and uniting oneself with it as emblemized by the mother-lover’ (p. 147). The giant Sir Valentine embodies the power of civilization to dominate, overwhelm, and subject; the fairy-lover, Dame Tryamour embodies the power of a civilization to comfort, protect and delight.” Arthur’s turn toward kindness and empathy represents a similar turn from the masculine to the feminine (more on that soon).

Beaver Hollow. Perhaps named for a line in “The Passing of Arthur.” Shortly before King Arthur dies, Gawain’s ghost visits him and says: “Hollow, hollow all delight!/Hail, King! tomorrow thou shalt pass away./Farewell! there is an isle of rest for thee./And I am blown along a wandering wind,/And hollow, hollow, hollow all delight” (33-37).

Castor’s Ridge. A minor figure in Arthurian legend is called Sir Castor. Castor’s Ridge may be named for him. It may also be named for the character in Greek mythology, or for both of these figures.

Brandywine Drop. The painter Howard Pyle “trained a generation of artists who eventually became some of the most famous and prolific illustrators in America. Though he taught in various places, it was a summer location at Chadd’s Ford, Pennsylvania, on the Brandywine River that gave to his followers the name of the Brandywine School. A number of his students illustrated Arthurian retellings” (Lupack 168-169). Pyle also wrote and illustrated four books for children about King Arthur. Brandywine Drop is probably named in part for him, especially since Arthur and Jim “Boy” Calloway have their duel there.

Pleasance. In the Caxton print of Malory’s Le Morte Darthur, King Arthur conquers parts of Italy, including somewhere called Pleasance. Helen Cooper says that this section is based on the Alliterative Morte Arthure. Cross-referencing that text identifies Pleasance as Piacenza (Benson), a town in Lombardy. It doesn’t have any readily identifiable significance to the place in the game, or to Pleasance House from Red Dead Redemption. (Pleasance is largely an allusion to the Garden.)

Giant remains. In a particularly disturbing story, King Arthur slays an evil giant (Malory 88). The Giant Remains Point of Interest may be an allusion to this episode. In the story, we see the mountain setting, the fire, the club, and people murdered by the giant. However, the giant in Malory’s story has two fires, and the people he’s murdered are mostly young children or babies. Also, King Arthur stabs him, and the game’s giant died from a blow to the head, presumably from the broken spiked club lying next to him. Still, it’s similar enough to be worth consideration. (The legends have been rewritten so often it’s entirely possible that in someone else’s version, the details match more closely.)

Mission Names

“The Wheel.” Fortune’s wheel is a common symbol in medieval (and later) literature. Arthurian legend often refers to the concept when discussing Arthur’s fall. For instance, in Le Morte Darthur: “But fortune is so variant and the wheel so mutable that there is no constant abiding” (494). Everyone’s fortunes rise and fall throughout life; nothing lasts forever. This concept is where the mission “The Wheel” gets its name. It also recalls the game’s first mission after the tutorial chapter, when the wheel comes off the wagon Arthur is driving. We’ve returned to where we began: driving a wagon with our family, running from trouble, but not in dire straits just yet.

“The King’s Son.” The phrase “the king’s son” appears several times in Le Morte Darthur and is the name of a mission in the game. The phrase isn’t particularly uncommon, so it may or may not be an allusion. Or it may be a double allusion: the words also appear in The Tempest.

Miscellaneous

Big shadow. Micah quotes a peculiar line of Dutch’s: that Arthur is “a big shadow cast by a tiny tree” ( “An American Pastoral Scene”). This is loosely taken from Idylls of the King: “their fears/Are morning shadows huger than the shapes/That cast them” (“To the Queen”). The irony is that the line continues, “not those gloomier which forego/The darkness of that battle in the West,/Where all of high and holy dies away.” RDR2’s story is exactly that “battle in the West.” Once again, Dutch fails to correctly read the people around him and the situation he’s in.

Gawain. Jim “Boy” Calloway mentions Sir Gawain in “The Noblest of Men, and a Woman.”

Arthurian legend. Probably the most obvious allusion in the whole game is John, Abigail, and Jack’s conversation about King Arthur at the beginning of “The Wheel.”

Have faith. In The Death of King Arthur, the narrator calls Morgan le Fay “Morgan the Faithless” (66). This may be the inspiration for Dutch’s frequent line.

Lion’s paw. In one rather strange episode in “The Story of the Grail,” a lion pounces on Sir Gawain. In doing so, it sticks its claws through his shield. Gawain cuts its paws off, and they remain stuck to his shield. This may be the inspiration behind the game’s (equally incongruous) lion and the Lion’s Paw Trinket.

New here? Visit the Table of Contents to read the essays in order, or the Index & TL;DR to explore the site by topic. New essays are published Wednesdays at 1 p.m. E.T./10 a.m. P.T. Sharing the site is always appreciated!

Bibliography

Expand to view sources.

- Anonymous. Alliterative Morte Arthure. Edited by Larry D. Benson. Revised by Edward E. Foster. Robbins Library Digital Projects, University of Rochester, 1994. https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/benson-and-foster-king-arthurs-death-alliterative-morte-arthur-part-i.

- Anonymous. The Death of King Arthur. Translated by James Cable. Penguin Books, 1971.

- Anonymous. “King Arthur and King Cornwall.” Edited by Thomas Hahn. Robbins Library Digital Projects, University of Rochester, 1995. https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/hahn-sir-gawain-king-arthur-and-king-cornwall.

- Anonymous. The Mabinogion. Translated by Sioned Davies. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Anonymous. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: A New Verse Translation. Translated by Simon Armitage. New York, W.W. Norton, 2007.

- Cantamessa, Christian, et al. “Red Dead Redemption.” Rockstar Games, 2010.

- Chestre, Thomas. “Sir Launfal.” Edited by Anne Laskaya and Eve Salisbury. Robbins Library Digital Projects, University of Rochester, 1995. https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/text/laskaya-and-salisbury-middle-english-breton-lays-sir-launfal.

- Chrétien de Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Translated by William W. Kibler. Penguin Books, 1991.

- Houser, Dan, et al. “Red Dead Redemption II.” Rockstar Games, 2018.

- Jones, Leslie. “Heads or Grails?: A Reassessment of the Celtic Origin of the Grail Legend.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, Vol. 14, 1994, pp. 24-38.

- Lupack, Alan. Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Malory, Sir Thomas. Le Morte Darthur. Edited by Helen Cooper. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Jones, Mary. “White Stag.” Jones’ Celtic Encyclopedia. 2004. https://www.ancienttexts.org/library/celtic/jce/whitestag.html.

- McShane, Kara L. “Deer.” The Camelot Project, Robbins Library Digital Projects, University of Rochester. https://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/theme/deer.

- Tennyson, Baron Alfred. Idylls of the King. Project Gutenberg, 1996. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/610/pg610-images.html.